The inevitability of fragmentation is perhaps matched only by the complexity of the effects that it has on individual species.

While we know that fragmentation adversely affects diversity, we do not yet understand how this plays out at the level of particular species.

Researchers from Wildlife Conservation Society-India, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore and Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), Mysore set out to study just this, and their work has recently been published in Biotropica.

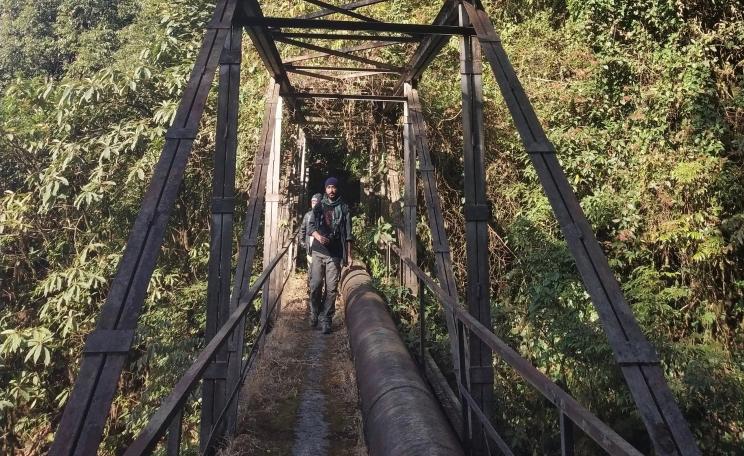

There are few places better suited to study fragmentation than Valparai in Tamil Nadu, India. An undulating plateau, Valparai has over forty rainforest fragments ranging in size from 1 to 300 ha (that make up a mere 4.5 percent of the plateau) embedded in plantations of tea (51 percent) and shade coffee (11 percent). The plateau itself is surrounded by relatively undisturbed forests of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve, Parambikulam Tiger Reserve and Vazhachal Reserved Forests.

Habitats

The authors chose 131 trees of four species that stood within the Anamalai Tiger Reserve, at forest edges, in forest fragments, or in tea or coffee plantations. They observed these trees for a total of 623 hours to determine which birds were important seed-dispersers for them, and how often they were visited by these birds in the different habitats.

They decided to focus on seed dispersal because where a seed lands is the single most important factor affecting the fate of the sapling that will emerge from it. In fact, so crucial is seed dispersal that it can determine which tree species will go extinct as a forest begins to fragment and which will persist.

Large-bodied frugivores are usually the first to be lost due to fragmentation and so it seems intuitive that large-seeded trees that depend specifically on them for dispersal would fare worse in fragmented habitats than small‐seeded plants dispersed by a diverse assemblage of frugivores. Such generalizations are exactly what the results from this study force us to question.

One of the trees chosen, Myristica dactyloides, has a large-seeded fruit rich in lipids that Hornbills are partial to. The tree was most visited by Malabar Grey Hornbill, a relatively large bird that has managed to make a home for itself within this production landscape, foraging and even breeding in the small fragments and in the native-tree cover of the surrounding coffee plantations.

The inevitability of fragmentation is perhaps matched only by the complexity of the effects that it has on individual species.

The study found that more Hornbills visited Myristica trees that had less surrounding forest cover, irrespective of how much fruit was on the tree. The authors think that this may be because the tree must seem even more attractive in a resource-poor habitat.

Fragmentation

Another tree chosen was Persea macrantha, and the results for this small-seeded species too were unexpected. The most effective disperser for Persea was the Yellow-browed Bulbul, a small endemic bird that prefers forests and doesn’t usually venture out into disturbed habitats.

Therefore, it understandably didn’t venture out to trees with less forest cover around them and was replaced by generalists like the Southern Hill Myna and the White-cheeked Barbet that visited the trees in the fragments.

While all three of these birds visiting Persea (Yellow-browed Bulbul, Southern Hill Myna and the White-cheeked Barbet) were tracking resources – locating trees in the landscape and then zeroing in on trees with large fruit crops – the authors found that the visits by the Myna and the Barbet did not compensate for the loss of seed-dispersal provided by the Bulbul. Hence, we have a small-seeded tree that is clearly facing the brunt of habitat fragmentation.

Next to habitat loss, fragmentation is the biggest threat that our wild habitats face today; our burgeoning populations, a paucity of resources, and questionable environmental clearance procedures point to their ineluctable fate. The inevitability of fragmentation is perhaps matched only by the complexity of the effects that it has on individual species.

As this study clearly demonstrates, a whole array of factors, from the composition of the fragment, the nature of the intervening habitat, to the physiological traits of the trees and their associated frugivore dispersers determine how fragmentation will affect any particular species.

Studies like this are also vital to better understand dispersal interactions in such altered landscapes so that we can mitigate the effects of fragmentation and begin to revive degraded landscapes. They tell us, for instance, which birds or trees can help pave the way for ecological restoration of disturbed habitats.

This Author

Sartaj Ghuman is a freelance biologist, writer and artist based in India.