Since September 11, 2001, there has been a major perceptual change around the world. All of a sudden we have become acutely aware of our vulnerability. However, the roots of this vulnerability are still not discussed by our political leaders and are rarely mentioned in the media. More than a year has now passed since the terrorist attacks on the US, and in that time the broader context of the new international terrorism has been discussed in many careful studies by scholars and political analysts. And yet the Bush administration persists in portraying terrorism as the result of evil forces operating in a vacuum. In doing so, it perpetuates a climate of fear among the American electorate that prevents any substantial discussion of the US’s serious social, economic and ethical problems.

There is no simple defence against terrorism. This is because we live in a complex, globally interconnected world in which linear chains of cause and effect do not exist. To understand this world we need to think systemically – in terms of relationships, connections and context. Understanding terrorism from a systemic perspective means understanding that its very nature derives from a series of political, economic and technological problems that are all interconnected. To understand the root causes of our vulnerability we need to understand the conditions that breed hatred and violence, as well as the characteristics of a technological infrastructure that makes large-scale attacks a highly effective terrorist weapon.

Thinking systemically means realising that security, energy, agriculture, economics and climate change are not separate issues but different facets of one global system. It leads us to understand that the root causes of our vulnerability are both social and technological, and that they are the consequences of our resource-extractive, wasteful and consumption-oriented economic system.

Millions of people around the world see the US as the leader of a new form of global capitalism that has significantly increased poverty and social inequality. It has generated unprecedented wealth at the very top while forcing billions of people into desperate poverty. Consequently, the relationships between the rich and the poor are increasingly shaped by fear and hatred, and it is not difficult to see that many of the desperate and marginalised are easily recruited by terrorist organisations.

The main thrust of the WTO’s free-trade rules has been to dismantle local production in favour of exports and imports. This has greatly increased the distance ‘from the farm to the dinner table’. In the US, the average ounce of food now travels over 1,000 miles before being eaten. This puts enormous stress on the environment. New highways and airports cut through primary forests, new harbours destroy wetlands and coastal habitats, and the increased volume of transport further pollutes the air and causes frequent oil and chemical spills.

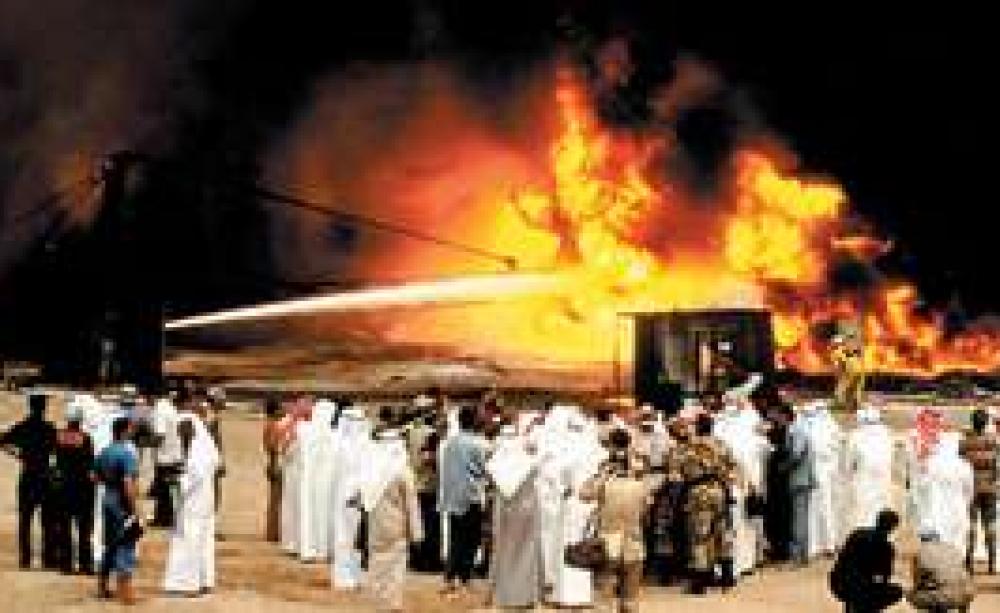

The dramatic increase of transportation and energy use has resulted in a highly centralised and inherently vulnerable network of supply lines. It is evident that an energy infrastructure consisting of gigantic pipelines, refineries, dams and nuclear plants is more vulnerable than a pattern of decentralised solar power. And a food system dominated by a few mega-farms with extravagant freight needs is much more prone to terrorist attacks than one featuring a multitude of small farms and local farmers’ markets.

In the US, these vulnerabilities are exacerbated by misguided energy policies that have decisively shaped the country’s foreign policy. Successive administrations have perpetuated an unnecessary dependence on oil. In exchange for unlimited access to this so-called ‘strategic resource’, the US has supported undemocratic and repressive regimes throughout the world – particularly in the Middle East. These policies continue to fuel anti-American hatred in populations that are deprived of basic human rights.

According to recent estimates by the United Nations Development Programme, every poor person on earth could have clean water, basic health services, nutrition and education for a cost of about $40 billion a year. Instead, the Bush administration launches a war in Iraq that will cost an initial $200 billion (and billions more for many years to come) in order to assure control of an unrestricted flow of Persian Gulf oil.

If we look only at the price Americans pay at the pump, oil is currently cheap in the US. But the military costs to protect each barrel of oil are actually higher than the cost of the oil itself; and when we factor in the environmental costs, the real price of oil becomes prohibitively high. However, it is absolutely feasible with technologies available today that the US could completely sever its dependence on foreign oil. In fact, Amory and Hunter Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute estimate that the US would not need to import any Persian Gulf oil at all if it increased the fuel efficiency of its light vehicles by a mere 2.7 miles per gallon (mpg). To appreciate how easy this would be technologically, we need to realise that the average fuel efficiency of US cars sold in 2001 was 20.4 mpg, whereas today’s super-efficient hybrid-electric cars achieve fuel efficiencies over 40 mpg. But instead of raising US fuel-efficiency standards, Bush and his oil men in the White House prefer to spend $200 billion of US taxpayers’ money on a war that could kill thousands of innocent people.

A shift of energy policy from the current heavy emphasis on fossil fuels to renewable energy sources and conservation is not only imperative for moving toward ecological sustainability, it is vital to nations’ security. More generally, we need to broaden the concept of security to include (besides energy security) food security, the security of a healthy environment, social justice and cultural integrity.

As US ecologist and educator David Orr points out, systemic thinking implies a shift of emphasis from security through protection by police force and military power to security by design. A community designed to be secure is one that is ecologically and socially sustainable. To ecologists the fundamental link between security and sustainability is not surprising, because sustainability means long-term survival. Over more than 3 billion years of evolution, nature’s ecosystems have developed ‘technologies’ and ‘design principles’ that are sustainable in the long run and hence resilient and inherently secure. Natural selection has seen to it that vulnerable systems are no longer around.

The choice is clear. If we continue to favour an economic system dependent on fossil fuels, centralised technologies and vulnerable supply lines we need to protect it with a huge worldwide police force at enormous expense and risks to civil liberties. If, on the other hand, we shift to a decentralised world economy based on renewable energy sources, sustainable agriculture and regional food systems we can create communities that no terrorist can threaten and which threaten no one else. We have the necessary technologies to do so. What we need is political will and leadership.

Fritjof Capra is a systems theorist and the author of The Web of Life.

This article first appeared in the Ecologist May 2005