I once saw a film of a European doctor teaching Samoans how to brush their teeth. Particularly striking was the fact that their teeth were white and shiny, while his were black. The trouble is that once people start using toothbrushes and toothpaste there is no looking back. The self-regulating mechanisms that once kept the teeth clean become redundant and, in accordance with the law of economy, they cease to be operative. Toothbrush addiction has set in!

Unfortunately, the toothbrush and toothpaste are unlikely to be isolated phenomena. The sort of society that produces them is also likely to manufacture countless other mass-produced artefacts. Among these will figure processed foods of different types, made from, among other things, refined carbohydrates, which are increasingly associated with tooth decay. As these form an ever more important part of our diet, so must there be a corresponding increase in our addiction to toothbrushes.

Eventually, these clumsy devices are not sufficient to maintain our teeth in good condition. Hence the need for dentists who specialise in inventing and implementing other devices. As their services become more generally available, so tooth decay must become correspondingly more tolerable. In this way we become addicted to dentistry.

Eventually even dentists are of no avail. Our teeth fall out, false teeth are resorted to, and as these become generally available, so there is a corresponding decline in our preoccupation with the preservation of the real ones. Brushing one’s teeth becomes less of a ritual. Refined carbohydrates can be consumed with a clear conscience, and dentists, rather than painstakingly repairing decaying teeth, can now indulge in an orgy of tooth extraction. In other words, we become false teeth addicts, and the extent of the addiction can be gauged by the fact that today there are 17 million toothless people in this country!

In much the same way, our society is becoming ever more addicted to myriad gimmicks intended to ensure our survival in ever less favourable conditions.Thus farmers now take far greater liberties with their soil than they did before artificial fertilisers were available. Everywhere farmers are neglecting to return manure to the land where it belongs. It is redundant, bulkier, messier and, in Britain at least, it doesn’t benefit from government subsidies, as artificial fertilisers do. In the meantime the soil, saturated with inorganic nitrogen, no longer depends on manure for its supply on nitrogen-fixing bacteria. These slowly become inoperative, and the system’s ability to ensure self-fertilisation is correspondingly impaired. Addiction to artificial fertiliser has set in.

In the same way, the more that pesticides are used, the more the natural mechanisms ensuring the control of insect populations become redundant. Since pesticides accumulate as one moves up the food chain, the predators that previously assured this control receive a far greater dose than do their prey, and their demise must lead to the latter’s further proliferation, and so our crops become hooked on pesticides.

And so it is with all other aspects of our technologically dominated life. The result is that the satisfaction of our ever more numerous addictions makes it imperative that the economy be maintained on a course of continued expansion. If there is the slightest respite,

withdrawal symptoms begin to appear. If ‘economic stagnation’ sets in, then these symptoms become so pronounced as to menace the survival of society. Unfortunately, economic growth cannot go on indefinitely, as our planet has a finite capacity to provide the necessary raw materials and to absorb the industrial and agricultural wastes.

Still more unfortunately, we are now approaching that point where countless physical, biological and social factors must bring it to an abrupt end, unless we act to ensure a transition to some sort of

steady-state society. To do this, we must contrive to recover from our addictions.

Clearly, recovery cannot be done all at once without causing the collapse of the whole system. To recover from them is not possible at all unless we gradually reintroduce the self-regulating mechanism

usurped by the modern technological intrusions to which we have become addicted. To create the conditions in which this recovery can occur must be the everyday goal of all those seriously seeking to solve the present environmental and social crisis.

Ecologist editorial, December 1971

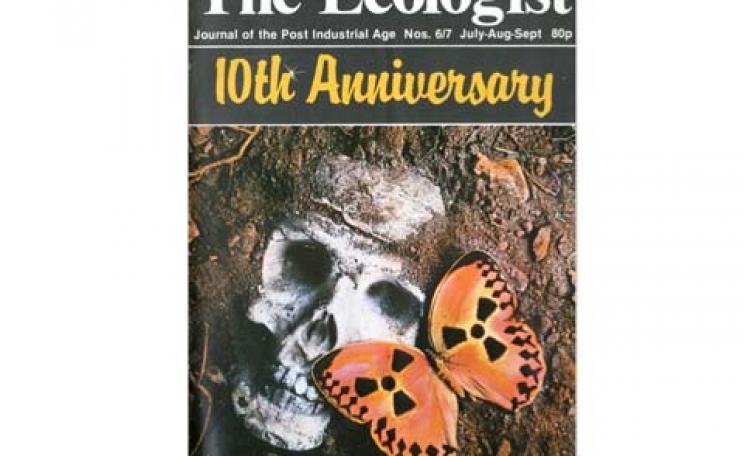

Special Reader Offer: Save 25%

The Doomsday Funbook

A thought provoking Christmas present. Acollection of editorials spanning the Ecologist magazine’s 35 years, together with the brilliant

cartoons by Richard Willson that originally accompanied them.

£7.43 (inc p&p) (RRP£9.99)

To order, please telephone

01795 414 963

And quote reference: ECODOOM

This article first appeared in the Ecologist September 2006