Few are the people who eagerly anticipate a trip to IKEA, the cheap, stylish Swedish furniture retailer, which with revenues of $23.1billion in 2010 and staff numbering more than 127,000, has grown to the size of a small country over the past five decades. Visits to IKEA’s giant, out-of-town stores can be headache-inducing, divorce-breeding, stressathons, yet they have become an integral part of modern life for students, young professionals and homeowners from Dubai to Durham. So should we be among them?

On the plus side, the company is doing pretty much everything it can to make its products, and stores, as energy-efficient and sustainably produced as possible as part of its programme of ‘neverending improvements’. The flat-packs that make it so easy to lug furniture home? They also mean that the company can transport more furniture from factory to store at a time, reducing the level of emissions generated. Brown cardboard, the company trumpets, makes the products cheaper and is environmentally friendly. The minimalist, lightweight designs the company has pioneered mean that less materials are used in the fabrication of each item of furniture, while again reducing the emissions involved in transporting them. Getting you to assemble the furniture at home again cuts emissions - by reducing the number of automated assembly lines IKEA uses - while lowering the cost of the furniture.

IKEA says that it is moving towards powering all of its stores with renewable energy, and has been working to cut its power consumption levels since 2005 - although it is yet to set a deadline for either target. In fact, there is a certain ambiguity to a lot of the company’s more ambitious-sounding sustainability plans. Take its scorecard system. In 2010, IKEA launched an internal tool to measure the sustainability of each product it sells based on a series of 11 metrics. In its sustainability report released the same year, the company said that it wanted everything it sold to be ‘more sustainable’ by 2015 - a slightly opaque measure, although it also aims to reduce the amount of energy used in producing its white goods by 50 per cent by 2015, and the amount of water used in all of its products over the same period.

IKEA says that it is moving towards powering all of its stores with renewable energy, and has been working to cut its power consumption levels since 2005 - although it is yet to set a deadline for either target. In fact, there is a certain ambiguity to a lot of the company’s more ambitious-sounding sustainability plans. Take its scorecard system. In 2010, IKEA launched an internal tool to measure the sustainability of each product it sells based on a series of 11 metrics. In its sustainability report released the same year, the company said that it wanted everything it sold to be ‘more sustainable’ by 2015 - a slightly opaque measure, although it also aims to reduce the amount of energy used in producing its white goods by 50 per cent by 2015, and the amount of water used in all of its products over the same period.  By the same token, IKEA literature trumpets plans to install solar panels on 150 stores and distribution centres worldwide to meet 10 per cent of its energy needs but by December 2010, only seven panels had been installed on just 17 buildings. The company plans to increase this to 40 by the end of 2011. IKEA also likes to sell its ethics, and by all accounts has worked hard to make sure that the materials it uses, and the labour used to produce it, is sustainably sourced and meets international regulations. The ‘IKEA Way’ is a set of rules and regulations for its suppliers, which it hopes to see fully enforced by 2012. They include rules on where wood is sourced from, and oblige suppliers to provide annual reports on the origin, volume and kind of wood used in their products. The Rainbow Alliance, meanwhile, audits the company annually. IKEA also has strict rules on child labour, and demands that all of its suppliers recognise the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. If a supplier is found to be using child labour, IKEA says it will be asked to end the practice or have its contract revoked.

By the same token, IKEA literature trumpets plans to install solar panels on 150 stores and distribution centres worldwide to meet 10 per cent of its energy needs but by December 2010, only seven panels had been installed on just 17 buildings. The company plans to increase this to 40 by the end of 2011. IKEA also likes to sell its ethics, and by all accounts has worked hard to make sure that the materials it uses, and the labour used to produce it, is sustainably sourced and meets international regulations. The ‘IKEA Way’ is a set of rules and regulations for its suppliers, which it hopes to see fully enforced by 2012. They include rules on where wood is sourced from, and oblige suppliers to provide annual reports on the origin, volume and kind of wood used in their products. The Rainbow Alliance, meanwhile, audits the company annually. IKEA also has strict rules on child labour, and demands that all of its suppliers recognise the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. If a supplier is found to be using child labour, IKEA says it will be asked to end the practice or have its contract revoked.

All of this is very well and good, but the key issue with IKEA from an environmentalist’s point of view is that the company encourages the mass-consumption of goods that generally need to be replaced after a few years, putting an increasing strain on the world’s natural resources. In her 2009 book, Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture, Ellen Ruppel Shell argues that IKEA - by some measures the world’s third-largest consumer of wood - sells products with a limited lifespan and that, by claiming its products are ‘sustainable’ and come from ‘renewable’ sources, effectively encourage consumers to replace like with like, rather than spending more on longer-lasting products. On a more anecdotal note, who has ever visited IKEA and left with just what they went to get? IKEA stores are famous for being designed to encourage visitors to buy all manner of goods they didn’t think they needed, and probably didn’t. Meanwhile, the company’s out-of-town stores make it all but inevitable that the average IKEA shopper will have to bring a car - try taking an IKEA bed home on the bus or train - to a destination which is much further away than they would normally go.

Clearly, IKEA is doing its bit to become an ethical and sustainable producer but at heart its low-cost, high-volume business is one which relies on the constant consumption and replacement of goods that use pretty much every natural resource you could care to mention, including wood, water, energy. IKEA’s argument - and it is a compelling one - is that because it mass-produces affordable goods, and makes those goods as sustainable as possible, it is ensuring that huge numbers of people are reducing the environmental impact of furnishing their homes.  Given that around 170 million people a year visit the company’s stores, this is a fair claim. IKEA reckons that if every single one of its customers replaced a single 60-watt lightbulb with the energy-saving alternative it would reduce carbon emissions by the equivalent of 750,000 cars.

Given that around 170 million people a year visit the company’s stores, this is a fair claim. IKEA reckons that if every single one of its customers replaced a single 60-watt lightbulb with the energy-saving alternative it would reduce carbon emissions by the equivalent of 750,000 cars.

But the company continues to stock ordinary light bulbs, and here lies the conundrum. Like other mass-producers, IKEA could simply stop producing less energy efficient or environmentally-friendly goods but in doing so it would become more expensive, and this in turn could lead to the loss of customers. The company is a business at heart, and so must keep up a constant balancing act between sustainability and profitability. Shopping at IKEA won’t save the planet but if you are strapped for cash and need to furnish your home it is probably the best choice available.

| READ MORE... | |

|

GREEN LIVING Behind the Brand: Google Unless you live on the moon, Google is an integral part of your day to day life, but just how ethical is the all-conquering search giant whose motto is ‘Don’t be Evil’? Peter Salisbury investigates |

|

GREEN LIVING Behind the Brand: L’Oréal It is the biggest beauty company in the world and owns numerous ethical brands including The Body Shop and Pureology, but do its own ethics stand up to close scrutiny? Peter Salisbury reports |

|

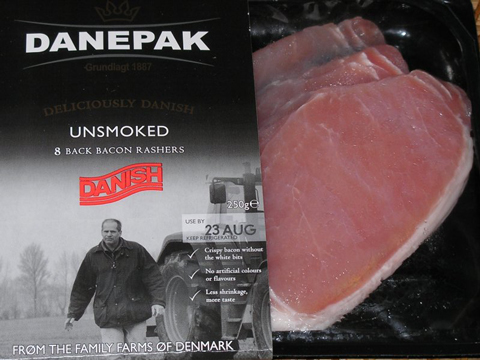

GREEN LIVING Behind the Brand: Danish Crown Can the owner of a slaughterhouse that despatches more than 80,000 pigs per week be remotely ethical? Peter Salisbury takes a closer look at pork exporter, Danish Crown |

|

GREEN LIVING New series Behind the Brand: McDonald’s In the first of a major new series following on from the ground breaking Behind the Label, Peter Salisbury takes a look at one of the biggest brands in the world – McDonald’s – and asks: has the burger giant done enough to clean-up its act? |

|

GREEN LIVING Green Business: Ecotricity It’s the biggest green energy company in the UK but that’s not enough for founder, Dale Vince. The next step, he tells Peter Salisbury, is to take on the ‘big six’ energy companies and show us all that renewables are the way forward |