The environmental movement has often been guilty of making people despondent, either by talking about 'problems' in a way that makes listeners feel powerless, or by presenting solutions as miserable duties. It needn't be that way.

Instead, we could try to make doing the right thing appealing, rather than merely necessary - and one way to do that is to offer people a chance to say hello to their neighbours.

Perhaps the greatest environmental and economic challenge of our age is that we have substantially depleted our oil reserves, and entered the era of 'peak oil'. Reading about this in the abstract, the problem sounds both dreary and chilling - a reason to retreat into ourselves and do nothing in particular besides panic.

Certainly, when I first found out about 'peak oil', in 2005, I was desperately worried. I told my wife that the future as we had always imagined it was an illusion. (This didn't go down very well.) I wanted to act, but felt lost until I heard about the startlingly upbeat approach of Rob Hopkins and the other Transition Town pioneers, who seemed to have found ways to turn this catastrophic prospect into an opportunity.

'Realistically, only a very small percentage of people will think that life beyond abundant oil could be preferable to what we have now,' Hopkins told me. 'But I don't think it has to be a dark age. It could be a most extraordinary renaissance.'

Hopkins and his allies used a technique that we could all use to find motivation, whatever our mission of change. They sent themselves, in effect, a cheerful postcard from the future. They used 'imaginary hindsight' to picture what the world could be like in a hundred years if humankind gets it mostly right - and they concluded that local communities will all be much more self-sufficient than today, and more close-knit.

Then they worked out backwards how to get there, year by year. The steps for change included: teach people to grow food, and make and mend clothes (and other items), hold workshops to give energy conservation advice, and form clubs to install renewable power facilities. In each case, as these strategies were put into practice, the leaders of the movement found out something remarkable: that people actually enjoyed coming together with a common purpose, picking up useful and engaging skills and (in the process) building a greater sense of community.

Delighted, I told friends about Transition, and was thrilled when one of them asked me to help him set up a group in his area, Belsize Park, not far from where I live in north London. Soon others joined us, and it was enormously reassuring to see that people shared our concern.

The high point was a meeting in a crowded hall. Hoping to spread awareness, and find allies, we had invited everybody we could think of who might have an interest in joining forces: local members of environmental lobby groups, people who promote Fair Trade, church groups, members of the local barter network, political parties, and anybody who lived locally who happened to hear about us.

In the months that followed, our group achieved a great deal, organising film screenings, talks and even a street fair. But I was impatient to do more than preach to the converted. With peak oil and climate change coming up fast, I wanted to see everybody growing their own food. What to do?

My next step was substantially inspired by a book called Soil and Soul, by Alastair McIntosh, who has been involved in extremely successful community groups in Scotland. A practising Christian, McIntosh has written about the imperative properly to re-imagine and act upon that old Christian dictum, to love your neighbour. When it comes to trying to change the world, he has argued, it's no good campaigners shouting through a megaphone at anonymous millions. They must start with those closest to them. If they are not good neighbours, then why should anybody listen?

I was powerfully struck by this point. Transition Towns emphasize local engagement, and McIntosh suggested taking that to the logical conclusion. I would do it! I would try to work with my neighbours. And not just the handful of people in my street who might be inclined towards environmentalism already, but my actual next-door neighbours.

I had moved into my house a few years earlier, and knew Martin and Val enough to say hello and have little chats. (The house on the other side was empty.) We'd been into each other houses, but not often or for long. We looked after each other's spare keys. I hadn't the faintest idea what they thought about peak oil.

So I walked round one afternoon and knocked on the door, which was opened by Val. I told her I had got hold of a film about how the world was going to run out of oil soon, and I wondered if they might like to pop round and watch it one day - any day. How were they fixed next week?

This may not have been the most attractive invitation Martin and Val ever received. But to their eternal credit they said they'd like to come round, the following Tuesday afternoon. They would bring a friend too, Val said, if that was alright, because she was interested in that kind of thing.

So the day came, and I bought some biscuits and made tea and we watched the film, which is pretty devastating, because it destroys all possibility of the future we might previously have hoped for. I was a bit worried about this, because as the late philosopher Raymond Williams once put it, the key thing is not to make despair convincing but to make hope possible.

Afterwards we had a little chat. I can't remember exactly what we said. But a few weeks later workmen came round and installed solar panels on Martin and Val's roof.

I was stunned. This loving-your-neighbour business was more powerful than I could have imagined. I had learned for myself that it's possible to extend your support network into unexpected places.

To be clear, I don't mean to suggest that we think of our neighbours as merely useful. At every moment, we choose to see others either as people like ourselves, or as objects in our own life's drama. They either count like we do, or they don't. I'm glad to report that Martin and Val counted very much. In fact, with hindsight, I think I am less pleased by their installation of renewable energy than by the fact that they agreed to come and watch a rather unpromising film; and that Martin subsequently invited me to lunch. Simone Weil once wrote that the sense of being rooted is a greatly overlooked human need - and, as I found, getting to know your neighbours is a great way to feel more rooted.

All the same. I wondered if I might get any more locals involved in my scheme, perhaps with a greater emphasis this time on the upside. That September, I collected apples from my apple tree and put them in a huge box, which I carried under one arm while holding my young daughter's hand in the other. We walked up and down the street, telling our neighbours we had more apples than we could use, and would they like some? I had calculated that a man holding a toddler's hand, and offering fruit at no cost, is not unduly frightening. Most neighbours seemed glad to take a handful of apples.

A few months later, I sowed dozens of tomato seeds in small pots. When the young plants appeared, I got hold of another box, grabbed my daughter's hand, and went up and down the street again. I told my neighbours I had grown 'too many' tomato seedlings. Oh dear! Would they like one? Nobody refused, and that year, several people in my street enjoyed growing their own food for the first time. Perhaps they were going to do that anyway - but I like to think I gave them a little push - and without even mentioning peak oil.

Your ideas for changing the world may feel desperately important. They may be desperately important. But if you can't find a way to engage the interests of the people around you - including, if not only, your next-door neighbours - they may never take off.

And perhaps they don't deserve to.

John-Paul Flintoff is on the Faculty of The School of Life. His book How To Change The World (Macmillan) is published in the UK and around the world

John-Paul Flintoff is on the Faculty of The School of Life. His book How To Change The World (Macmillan) is published in the UK and around the world

| READ MORE... | |

|

HOW TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE Why we need to stop trying to 'save the planet' and just realise our place in it In an extract from his new book the Jolly Pilgrim, Peter Baker argues that a Gaian consciousness is slowly emerging out of our efforts to overcome climate change and other environmental challenges |

|

GREEN LIVING Second skin: why wearing nettles is the next big thing John-Paul Flintoff journeys into a world of sartorial bliss, kitting himself out in eco-friendly fabrics of the future |

|

HOW TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE Can we cut cancer and heart disease rates just by going vegan? We've heard about the environmental and animal welfare problems with meat consumption. Now a new film, Planeat, presents a convincing health case to re-examine our love affair with meat and dairy, reports Matilda Lee |

|

INTERVIEW Clive Hamilton: 'solving climate change is out of the question' Author Clive Hamilton on why we've left it too late to stop climate change, his horror over geoengineering and the urgent need to become citizens rather than consumers |

|

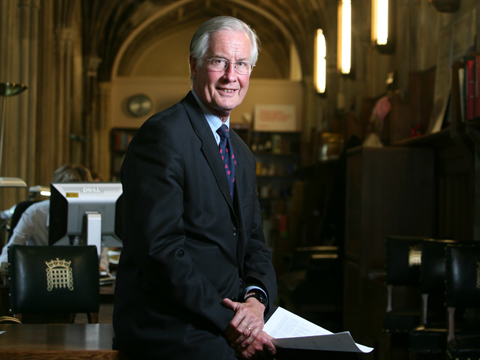

INTERVIEW Michael Meacher MP: humans only have 200-300 years left on earth Former environment minister Michael Meacher on the place of humanity in the universe, intelligent design, the survival of the human race, Gaia theory and uncertainties over climate change |