The new varieties yield very well when fertilized and irrigated, but these inputs are expensive, and so is the new seed. Most Indian farmers cannot afford such outlay, and have been forced out by those who could.

The Green Revolution of the late 1960s, based on short-stemmed varieties of wheat, first in Mexico and then in India, is seen as a triumph of western-style agriculture - and indeed of 20th century science and technology and of the whole, 'rational', Enlightenment agenda.

Here it seems is yet another demonstration that human beings are able to take the living world by the scruff of its collective neck and bend it to our will, and that this is what progress ought to mean.

The Green Revolution's leading light, Norman Borlaug, was duly awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. Similar methods then produced shorter-stemmed rice in the Philippines. Now there is much heady talk from on high of another Green Revolution in Africa - which indeed is already train.

But Vandana Shiva, who has watched events unfolding from the midst of the Indian farming communities that are most affected, has serious doubts.

The technique was brilliant and the original intent was surely good (I believe) but the outcome for many has been tragic. Indeed the greatest truth to emerge from the Green Revolution is not the 18th century conceit that we can mould nature and society to order.

Instead it is the 18th century observation of Robert Burns that "The best laid schemes o' mice an' men Gang aft agley, An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain, For promis'd joy!" In modern speak, in real life, the relationship between cause and effect is decidedly non-linear.

A major scientific achievement

The stems of wheat (and rice) needed to be reduced, it was felt, because the traditional kinds, which were often as tall as a man, grew even taller when fertilized. Then they fell over or 'lodged', so that the entire crop could be lost. So the traditional types yield commendably well when fertility is low, but can never give maximum yields because they can't stand additional fertilizer.

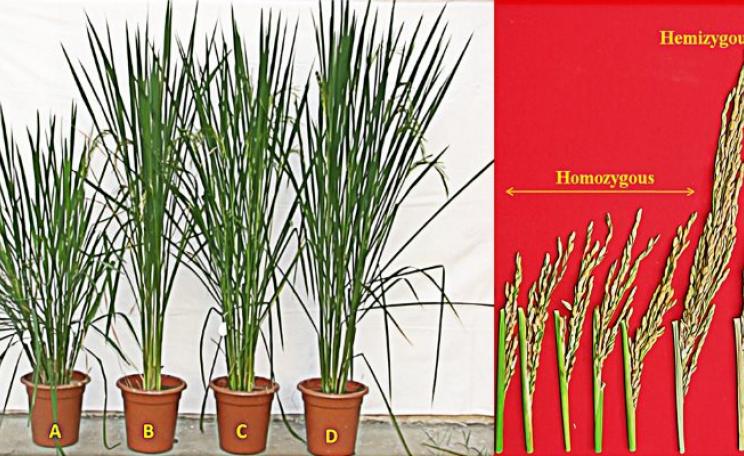

The new short-stemmed types were produced by crossing the traditional types with a 'dwarf' variety from Japan that had very short stems but was not itself suitable as a commercial crop.

But the crossing was far from straightforward. First the chromosome that contained the gene that shortened the stem in the Japanese dwarfs had to be identified. Then strains were produced that contained an extra copy of that chromosome.

Then these were crossed with strains of the traditional, tall types that lacked the corresponding chromosome - and some of the resulting offspring finished up with a complete set of chromosomes including one that contained the relevant gene.

Since bread wheat is hexaploid - six sets of chromosomes, inherited from three ancestral, diploid grasses - such manoeuvring is easier than in most other crops. But it still requires remarkable ingenuity and technique - and all this was achieved more than 50 years ago. The resulting offspring had stems of intermediate length: 'semi-dwarf'.

It is now generally accepted in high circles - in effect it is the modern mythology - that the new semi-dwarf varieties were a runaway success. Yields, we are given to understand, shot up. India rose from basket case status in the mid-1960s to become a grain exporter. India overall has become a serious player in the global economy.

The new varieties yield very well when fertilized and irrigated, but these inputs are expensive, and so is the new seed. Most Indian farmers cannot afford such outlay, and have been forced out by those who could.

Now the bad news - poor farmers forced from their land

But says Vandana, all is not so simple. The new varieties do yield very well when they are fertilized (and often irrigated), but these inputs are expensive, and so is the new seed. Most Indian farmers are small-scale and poor and cannot afford such outlay, so they have been forced out by those who could.

In India more than half a billion people work on the land and, realistically, agriculture is the only job that can usefully employ so many. Reduction in agrarian employment cuts right to the heart of the real economy and of everyday life.

Most of the bankrupt farmers, men and women, face either life in urban slums (a billion worldwide now live in urban slums; nearly a third of all city-dwellers) or, as hundreds of thousands have done in India, they commit suicide.

Neither was pre-GR Indian agriculture the disaster that later commentators have told us. Even in earlier days India had sometimes been a net exporter of cereal. The famines of the mid 1960s that prompted the GR were caused not by general failure but by prolonged, severe drought - which the new varieties cope with less well than the old types. How would the old types have fared with a little irrigation?

In general, semi-dwarfs yield more highly when conditions are good, but the old types outstrip them when times are hard - without irrigation, added nitrogen, or herbicide to kill the weeds which so easily smother the short-stemmed types; and most Indian farmers must farm in conditions that are far less than ideal. Besides, in a poor economy with plenty of cattle, plentiful straw is a bonus.

So the Green Revolution emerges not as an unalloyed, incontrovertible triumph of western know-how but as yet another morality tale. Of course it is not all bad. Modern agricultural science deployed judiciously really is among the world's great benisons.

But the great sin is arrogance, which the old Greeks called hubris. Modern science and high tech bring most benefit when they are designed to abet traditional practice: 'science assisted craft'. When they are applied single-mindedly, sweeping tradition aside, the results can be disastrous. But that is how they are so often used.

As Vandana says, science and high tech in the west have acquired the status of religion at its worst: a set of idées fixes that are taken unequivocally to be true, and seen to be above all criticism.

Africa's GMO revolution, courtesy of Bill and Melinda

Right now, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation and various governments, is planning to repeat in Africa what was done in India but on a far larger scale and across a broader range of crops.

This time round, the favoured technology really is genetic engineering. The mounting pile of evidence against GMOs is being ignored or actively suppressed as is the norm - again in accord with the quasi-religious myth which says that science is above normal criticism; with the additional, neoliberal myth that all will be well if we simply go where the money is and follow the market.

Bill Gates no doubt thinks he is doing good (and doubtless is in line for a Nobel Prize) but AGRA's endeavours seem likely yet again to transfer such wealth and power as they have from vast numbers of African farmers to a few high-tech companies and their government partners. The dispossessed African men will join the militia to fight any one of a hundred inchoate causes and the women will just have to do the best they can.

Vandana belongs on an honourable shortlist that includes Tolstoy and Gandhi, Albert Howard and Rachel Carson, and millions of farmers worldwide who see that agriculture is the most important thing that human beings do and that we cannot let it be driven by technological myth and commercial hype.

For those who seek to bring about the sea change that the world so desperately needs, The Vandana Shiva Reader is essential reading.

The book: The Vandana Shiva Reader is published by the University Press of Kentucky.

Colin Tudge is (with Ruth West and Graham Harvey) a co-founder of the Oxford Real Farming Conference and writes at the Campaign for Real Farming.