Thousands of people occupied the ancient beech forest of Retezat to defend it from loggers. Protesters turned out in their hundreds of thousands in cities across the country.

Home to the continent's largest remaining area of old growth forest, Romania has, for 25 years now, been great news for any European who wants to see bears and wolves and lynxes and would rather not fly.

But those forests were never just for eco-tourism: they were good news for Romanian cabinet-makers, too, until about 10 years ago.

Since then, Romanian exports of timber have more than doubled, while Romanian government figures show that the country's exports of wooden furniture have undergone a mysterious decline.

The explanation is an Austrian company and self-styled 'green leader' Holzindustrie Schweighofer, which began operations in Romania in 2003. Its gigantic sawmills and factories now have the capacity to process all the softwood harvested in the country. (And senior management figures at the company have been filmed stating that their ambition is to do exactly that).

As well as timber, its facilities also supply 'bio-energy', in the form of briquettes and pellets, to well-meaning customers across Europe.

Hijacking the 'restitution' process

But there is a longer story to tell about this. From East Germany to Czechoslovakia, from Hungary to Bulgaria, environmentalists played a crucial role in the undermining of Soviet rule in Eastern Europe.

It's a story we ought to know much better than we do. Communist Romania's Ceauş;escu regime was so severe that such activism was not possible until its fall. Since then, Romanian civil society has had everything to learn.

Schweighofer understood this only too well. It could rely from the start on the collusion of politicians eager to welcome investors on almost any terms. The Austrian company was able to both dictate the price it paid for timber and hijack the ‘restitution' process, which was supposed to return property confiscated by the communists to its former owners or their descendants.

Legal owners vs corporates

By 2010, however, more land was being requested for restitution than had ever been confiscated: according to a report by the Washington-based Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), which has conducted a three-year study in Romania, Schweighofer's proxies have been directly connected to many fraudulent claims.

Previous owners with genuine rights to their former land, meanwhile, are still mired in legal disputes. A new law, further weakening control of this process, was passed in 2013, signed into effect by Viorel Hrebenciuc, a politician indicted in one of the largest restitution scandals of the last 25 years.

The Romanian parliament has sought to restrain the company and rebuild its furniture-making industry through a new forest law, passed last year, though not without lobbying by the Austrian embassy, and threats by Schweighofer - not, thus far, realised - to disinvest. Even so, for many Romanians this new law is too lenient.

The lucrative business of managing national parks

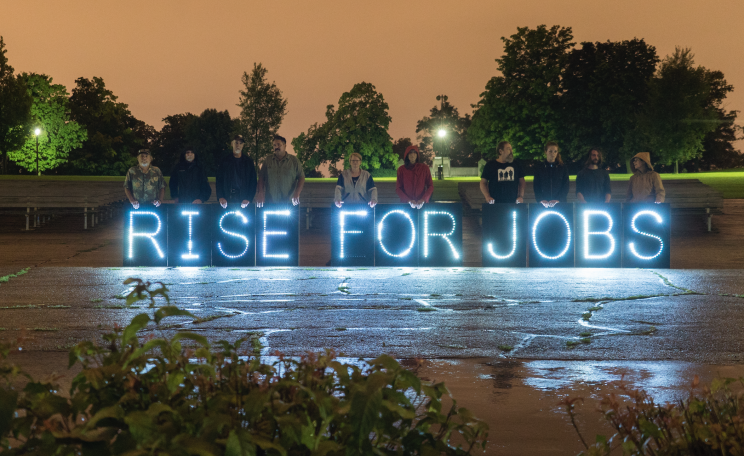

Thousands of people occupied the ancient beech forest of Retezat to defend it from loggers. Protesters turned out in their hundreds of thousands in cities across the country.

No account of this can ignore the bizarre hybrid that is Romsilva. Both a government agency and a private company, Romsilva oversees the auctions at which permits to cut trees are sold and administers the country's forests, 28 national parks included. It also negotiated the terms of Schweighofer's entry to Romania's timber market.

Potential conflict of interest? Romsilva doesn't do things by halves. Its profits multiplied by five between 2008 and 2014. And it earns five times more from timber extraction inside parks and other protected areas than it spends on managing them.

Schweighofer publicly decries corruption. It has conceded that "irregularities" may have occurred, which in some cases it has claimed were due to "typing errors". The company's website "guarantees" that it "never knowingly" buys illegal wood. Yet when EIA investigators with concealed cameras posed as timber merchants offering to cut more than was allowed, Schweighofer managers responded that there was "no problem".

The company has since argued that these remarks were taken out of context.

Tracking illegal shipments

Environmentalists have estimated that somewhere between 30% and 50% of the wood harvested in Romania is now done so illegally.

The Romanian journalist Gabriel Paun - also a leading environmentalist - followed a shipment of wood from inside a nature reserve to the gates of a Schweighofer mill. He explained the origin of the wood to the guards, and was pepper-sprayed for his pains.

When I asked Romanian forestry officials about this, it was darkly hinted that Paun had been "pushing his luck". Other journalists investigating the country's timber industry have also been threatened.

There would be plenty of darkness to dwell on here if it were not for the response of countless concerned Romanians. Thousands of people occupied the ancient beech forest of Retezat to defend it from loggers. Protesters have turned out in their hundreds of thousands in cities across the country.

Directia Nationala Anticoruptie, the anti-corruption agency, has uncovered a thriving trade in faked logging permits, signed in each case by the local Romsilva bureau. Some 27,000 phone calls were made when a number was set up at the Romanian ministry of environment to enable members of the public to ask about the status of any shipment of wood seen on the road. A quarter of shipments reported were illegal.

A 'woodtracker' app will allow the same online. NGOs have organised press conferences in Vienna calling on Schweighofer and the Austrian government to respect European timber regulations.

Taking action of all fronts

Schweighofer claims that all its forests in Romania are managed sustainably. This was never even notionally true for 98% of the company's supplies, which come from forests the company does not own, via roughly 1000 suppliers, many of whom are now under investigation. It was technically true for just 2% of its wood supply, which was sourced from the company's own forests.

These did indeed have FSC certification, until a team of scientists surveyed one of these 'sustainably' managed forests, at Campusel. They found evidence of poaching clear-cutting, a new road 32m wide in places, and large drums of chemicals lying about. Their findings were published in the Romanian Academy Journal and both Agent Green and WWF Germany lodged complaints with FSC. The company's FSC certificate was withdrawn in June.

The effort, then, is on all fronts. Evenimentul Zilei journalist Vlad Stoicescu's 2015 essay The World of the Woodcutters was awarded a national prize. Stoicescu travelled over 1,000 miles, talking to foresters and timber merchants, many of them "not proud of what they do". One of the most striking passages in his essay is about the fear, the blackmail, the threats of violence. But he reports also on the inspections of their factories, under the new law, by government officials.

From the street and YouTube to literary magazines, science departments and the national parliament: Romania has had a lot of learning to do on the environment. It has, by now, something to teach us, too.

Horatio Morpurgo writes on European environmental and literary topics.

This article was first published in Resurgence & Ecologist magazine, July/August 2016. A version of this article, with links to reports on Romanian Forestry, can be read on the Resurgence website.