.

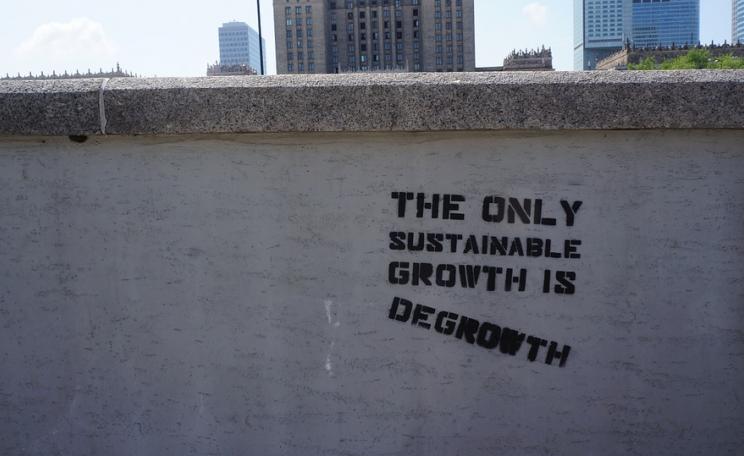

Our edible forest garden experiment in Budapest is part of a doctoral research project on urban agroforestry at the Szent Istvan University of Budapest, in the Faculty of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism. It was constructed in partnership with Budapest’s 14th District Council and the social Degrowth cooperative Cargonomia.

The garden opened with its first tree planting event last November. The event the result of a year’s of work in networking, cooperating with different partners and actors.

Our goal is to bring together planners, decision makers and experts in agroforestry and permaculture to rethink the use of public spaces in the city and democratise urban agriculture through citizens initiatives and involvement.

Dynamic network

We met with several researchers in agroforestry, and exchanged ideas with local NGOs whose work focuses on environment and permaculture in Budapest and with local farmers. We also connected our project with a dynamic network of community gardens in Budapest.

In October 2017 we presented the project to local authorities and decision makers and found support for implementing agroforestry in the city of Budapest.

Agroforestry is an ancestral practice that is being re-introduced in the European rural areas. The practice is based on the ecological interactions between woody perennials and annual plants and breaks with monocultural practice.

The benefits of this practice go beyond performance and yields. The plot is structured to create a resilient and autonomous ecosystem. By valuing biodiversity, the risk of epidemics is lower, diversity of seeds is preserved, water management is more economical and ecological, and the use of pesticides is unnecessary and avoided.

Agroforestry respects the seasons, the cycles of plants and the soil. Food production is then better integrated within the rural landscape and the existing ecosystems. The benefits are also social because this reconversion of land has potential to create new job opportunities and a new era of experimentation.

Overcoming skepticism

The public forest garden project in Budapest was inspired by several Tropical countries that have maintained a strong agroforestry practice in urban areas and forest garden practices in their homegardens.

In temperate countries, the concept of forest garden was introduced by the English botanist Robert Hart in the 1960s. Inspired by this model, we created a plantation plan with a diversity of endemic plant strata: wide canopy trees, fruit trees, berries, shrubs and vines.

The project was built in consultation with the partners, in particular the municipality. The use of visuals helped in understanding the purposes of agroforestry and presenting a vision. It was useful to overcome skepticism around growing edibles in an open public space: it felt necessary to explain the choice in species, their function in the land, the reasons behind the choice of agroecology principles, the benefits for the users and the prevalent support of the people mobilized behind the project.

The project is also about enhancing the local culture and adapting to the context by including a convivial dimension.

The land allocated by the district was a dried-out wetland in a residential area. It was mainly used by residents to walk their dogs and as an illegal parking lot. Thanks to an in-depth study of the terrain and the context, we chose plants adapted to the micro-environment, which are resilient to urban pollution and to drought, in order to limit the pressure on the ecosystems.

Public space

The garden will host a large variety of species, with free plantation areas for the people. Based on the principles of permaculture, other plants will be chosen according to their benefits for pollinators, their repellent characteristic, and their contribution to airing the soil, the nutrient supply and the retention of water. The project will evolve throughout a number of years.

Another challenge is to renew the ecosystem by planting edibles directly into the ground, without the need for materials, bins or planters, which can be very expensive.

The project was established on a low budget and relies on the networks of know-how and mutual aid, in lines with the philosophy of Cargonomia and based on the principles of degrowth. Accordingly, we did not apply for a grant. Instead, the tools and basic materials are shared between our partners and the neighbors.

With a long-term contract, the project leads to a new appropriation of the public space and another form of governance by the commons.

Ecological transition

Frequent visitors to the garden felt the space gradually change. We began the plantation with four fruit trees. The mayor and members of his team along with neighbors and local media participated in this first day.

The management of the edible forest is based on spontaneous initiatives and self-management. On the first day the neighborhood participants showed interest in the practice and attachment to the new trees. They brought water to the trees, and a volunteer gave out leaflets that we had prepared about the project.

The next day, one of the neighbors prepared and installed stakes by himself with pride.

We must adapt and understand the changes of ecosystems, limit loss in biodiversity and prepare for extreme periods in order to balance our climate. Decision makers, planners and landscape architects have the power to allocate public lands as common property. Reducing the consumption of urban spaces to open green and edible spaces reduces our vulnerability to climate change.

Botanists, ecologists, biologists, landscape architects and gardeners have a role to play in ecological transition and environmental education.

City planning

Through educational programs and consultations with horticultural experts it is possible to plan the city on the basis of natural ecosystems and to support individuals in developing their resources and depending less on market products.

We must rethink cities with a variety of vegetation and public green spaces, and enhance exchanges between the cities and the countryside to reduce the pressures on organic farms and rural agriculture.

Food industrialization should only be used in times of crisis because it consumes more energy and damages biodiversity. This raises the question of the conversion and conviviality of public spaces otherwise used to house parked cars.

Creating a public edible space enables social emancipation. Gardening creates a spontaneous relationship between individuals: people gather together and meet; the gardens create a space to initiate communication and exchange ideas.

This initiative encourages a new way of appropriating public space. We use simple tools which are better for the soil and the environment but also for the intellect. Manual work stimulates reflection and gives us time to feel and observe, just as hand-drawing allows the artist to discover and create.

We can imagine the public space differently and create another form of occupation; encourage change in land use for an ecological city and social well-being.

Empowering democracy

By supporting the re-appropriation and self-management of spaces, we can open or reconvert spaces and allow users to rebuild their environment, bring services closer and reduce expenses.

We must diversify the functions of public green spaces and vegetation and connect them with greenways and corridors. The connection between these places allows the exchange of resources and services. This pilot project is an experiment that aims to influence city policy.

The latest and most alarming IPCC report called for an end to deforestation. We think that this also concerns the city, or how to rethink a fertile, organic, autonomous and friendly city. This is vital as we face the collapse of our thermo-industrial civilization, but also we develop new means for living together peacefully, empowering democracy, and supporting relationships between people and the commons.

These Authors

Paloma de Linares is coordinator of the agroforestry project and a PhD student in Szent Istvan University of Budapest, in the Faculty of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism. Vincent Liegey is co-author of “Degrowth Project” (Utopia, 2013) and a Cargonomia coordinator. This article was first published in French in Bastamag