-

Things haven’t changed all that much in Sarawak these past twenty years. Logging companies keep nibbling away at the forest in this part of Malaysian Borneo, and the same strongmen are still in place after decades, benefiting from this massive deforestation.

These are same people and the same companies that used to track Bruno Manser relentlessly, until he vanished without a trace.

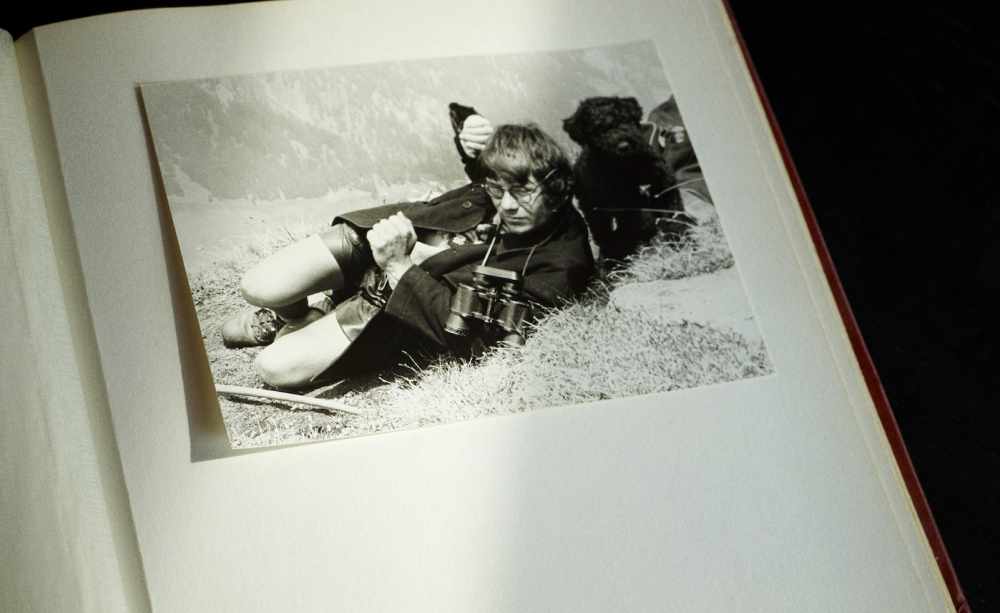

Manser is a well-known figure in Switzerland but not so much beyond the Swiss borders. He was a shepherd in the Swiss Alps who became a nomadic hunter among the Penan people in the Malaysian rainforest, seeking to lead a life without money and reluctantly turning to environmental activism.

Final day

Manser's struggle for the Bornean rainforest resonates today more than ever, as the forest has shrunk so much that of the 10,000 Penan people of Malaysia, only twenty are still nomads.

On 25 May 2000, in the mountains of Borneo, Manser needed to be discreetly guided outside of the small village of Bario. A price was put on Bruno Manser’s head by the Malaysian authorities after he had spent six years amid the Penan, the last nomads of the island, struggling against logging companies.

Manser had to hide to make his way to an important meeting of several nomadic groups. Thanks to his contacts, he had helped mobilize the scattered communities. But he would never make it there.

His trail stops when, in the early afternoon, his Penan guides let him head off alone towards the sacred mountain of Batu Lawi. His friends who were waiting for him were the first to raise the alarm. They combed the forest without finding a single trace of their friend, but on the ground everything indicated that a large group of people had recently passed through the area.

The Penan also watched in disbelief as many helicopters flew over the region of Batu Lawi. Months went by before their concern was shared, and Bruno Manser was officially declared dead in 2005.

Saviour?

If looked at carelessly, it can be tempting to portray Bruno Manser as a typical white-saviour figure: a young European man, travelling to the tropics, getting involved in the indigenous struggle for land rights, travelling back to Switzerland to raise awareness about their cause and getting in the spotlights while speaking in the name of the native people.

However, it would be a deep misunderstanding of who he was, and of how Bruno Manser’s destiny was deeply bound to the fate of the Penan people.

In 1984, several months after he first joined the nomad community led by Along Sega, the Penan gathered to give Manser a nickname. From now on, Bruno would be ‘Laki Penan’, the Penan man.

Indeed, since he joined them, Bruno Manser adopted the traditional hairstyle and the bark loincloth, and walked barefoot like the community elders. He recognized the messages they left in the forest using leaves and branches to inform the other groups about their numbers, their activities, the direction they were following.

He spoke Penan, lived among them and like them. Dark-haired, muscular, rather short, those who saw him at the time said that only his glasses distinguished him from his travelling companions.

Harmony

In the meantime, the young Penan were trading in their loincloths, feathers and blowpipes for trousers, T-shirts and rifles.

While Bruno Manser lived in harmony with the community elders, the next generations were no longer ready to fight in order to preserve their ancient traditions.

The development praised by politicians appealed to them. Life seemed easier in a house in town, especially when one had spent a lifetime fighting the logging companies and game was getting rare.

Manser no longer understood this generation of Penan and their longing for watches and sweets and who sometimes even worked for the logging companies. He was so depressed by the disastrous turn of the community that, when he disappeared, some his friends initially believed that he had committed suicide.

Struggle

Since the 1980s, many Penan communities have been struggling non-violently to prevent logging on their territory, blockading roads to stop trucks from entering their land.

Despite their small numbers, their presence still bothered the logging companies and their main support, the regional government. Hundreds of Indigenous people have been arrested, some have been killed, and others have disappeared without a trace.

Like the Penan, Bruno Manser became a political problem for the Malaysian authorities. Even though he never wanted this role, the fact is that he had helped to rally several ethnic groups, which were often isolated in small communities, to jointly defend their common interests.

He who imagined himself living contemplatively in nature became an activist. Word went round all the police stations: the priority was now to get hold of this troublemaking European. In 1986, he was public enemy number one.

In 1990, Manser was exfiltrated and started campaigning for native land rights from Switzerland. There, the Penan struggle found a resonance which led the Swiss government to pass a law on timber certification. However, in the rainforests of Borneo, the situation seemed irreversible.

Nomadism

At the time, it was estimated that 85 percent of the Penan habitat had been transformed by logging. Nomad populations were stuck in tiny pockets of impoverished forests, struggling against the thinning out of the game, poverty, and the pressure to settle.

In May 2000, the month Bruno Manser vanished, a vast construction of twelve hydroelectric mega-dams was relaunched and the logging companies nibbled away at the forest again – the forest the Penan people rely on for food, medicine and the materials they use to build their homes.

In 2011, Manser’s close friend Along Sega passed away. Four years before that, another nomad chief, Kelesau Naan, was found murdered, having opposed logging companies for decades.

Since the disappearance of these charismatic and traditionalist elders, Penan nomadism is only a memory, like the virgin forest and like Bruno Manser. The settled communities are now trying to reinvent a new Penan way of life, and to preserve the remaining secondary forests they still rely on.

Further west, in the town of Miri, the small Penan diaspora comes together around the Tajem FC football team. Tajem, like the poison traditionally used by the Penan people for blowpipe hunting. Having come to Miri to study or seek work, most of these young men will stay on in the city, and tajem will evoke for them a distant memory of their ancestors, and some memorable matches in the local championship.

This Author

Isabelle Ricq is an independent photographer and writer. She is the co-author with photographer Christian Tochtermann of the book Letter to Bruno Manser, which recounts Manser’s history and documents the current state of the territory for which he probably lost his life.

Image: Ricq & Tochtermann.