It is urgent to wean our economic system off its dependency on growth.

For every euro that makes GDP grow, raw materials and energy are used, and waste and pollution are generated. All economic activity has a real impact on the environment.

There is a growing consensus that an absolute decoupling of GDP growth from environmental impact is not possible, at least at a global level. Given the current overshoot of several planetary boundaries and the fast-shrinking carbon budget, it is urgent to wean our economic system off its dependency on growth.

Complete the Ecologist's 2020 Reader Survey.

Abandoning the pursuit of endless economic growth does not mean accepting poverty and a miserable life for citizens. There is no shortage of ideas for ways to significantly improve quality of life without GDP growth – in fact, the pursuit of growth in GDP at any cost can even lead to lower levels of wellbeing for citizens.

Debt

One aspect that too often goes unnoticed in the ecological debate is money itself, conceived of by mainstream economics as a neutral veil that sits over the ‘real’ economy. In fact, the design of our monetary system structures our economy in far deeper ways.

Our current system creates high levels of private and government debt. If the economy grows at a faster pace than public debt, this outstanding debt becomes smaller relative to GDP.

It is urgent to wean our economic system off its dependency on growth.

Consequently, governments are incentivised to pursue GDP growth to make high levels of public and private debt more manageable. This is one factor that locks us into a vicious cycle of endless economic growth and ecological destruction, only to keep up with our mounting pile of debt.

Where does this debt come from? The vast majority of the money supply exists in the form of electronic bank deposits, which hints at a little-known truth: banks create money when they make loans. When a customer takes out a loan, the bank credits their bank account with a deposit. This is a liability on the bank’s balance sheet, but also adds a corresponding asset: the obligation to repay the loan (debt).

Private banks seek profit. They make that profit on the ‘spread’ between interest paid to them on loans and the interest they pay to savers. Therefore, incentive schemes and targets encourage bank staff to sell more loans; unsolicited marketing and sales strategies encourage households and businesses to borrow more.

Profit

None of this would be so problematic if these private organisations weren’t administering a public good in the form of the payments system. For fear of that system collapsing, governments insure banks against their losses, leading to deposit insurance schemes and bailouts of so-called ‘too big to fail’ banks. In our current monetary system, losses are socialised while profits are privatised.

This arrangement means that debt climbs faster over time than it would if money was not largely created by loans. The subsequent debt is both public and private. Although advocates of austerity scapegoated public debt for the recession, debt owed by the private sector is by far the greater worry.

In either case, governments are motivated to promote growth to reduce the level of debt. Given what we know about the carbon and resource intensities of current growth models, we need to break this cycle to prevent the total breakdown of climate and planet.

In short, given the political and economic logic of a highly indebted system, governments need a way to promote a sustainable, equitable transition while reducing the overall debt burden. Luckily, such a tool exists, sitting right under the noses of elected policymakers.

Since the financial crisis, central banks have used their infinite firepower to pump trillions of dollars’ worth of new money into the financial system. This took place through the mechanism known as quantitative easing (QE). One channel for QE to take effect involves providing the banking sector with a greater supply of liquid assets, which should encourage banks to make loans. Stimulus since the crisis has inflated the debt-centric financial economy even further.

Money

The alternative would see central banks create money for investment in the ecological transition. The creation of new money for governments to spend as planned investment can be termed ‘Sovereign Money Creation’ (SMC).

SMC entails that money is created by the central bank and credited to the government’s account to be spent into the economy. There is no increase in private sector debt levels when new money is created. This would help governments escape the dependency on growth to reduce nominal debt-to-GDP ratios.

Oversight of how this new tool is used is vital. It would require a stringent institutional framework to prevent monetised budget deficits from overheating the economy or being spent on crude political patronage. As Adair Turner has claimed, ‘all the really important issues are political, since the technical issues surrounding monetary finance are already well understood.’

While central banks should decide how much money to create in order to meet their mandated objectives (which could, of course, always be altered from those they have now), democratically elected politicians should have control over how it is used. In the Eurozone, this would require new treaties to establish a new role for the European Central Bank, or national central banks working as part of the ECB system, in issuing new debt-free public currency.

Nevertheless, even if constrained by legislation, allowing central banks to create money to be spent into the economy in the public interest will disrupt the idea that ‘there is no money’ for the things society needs, like social housing, healthcare, and infrastructure for a low-carbon economy. To put it more simply, the ‘magic money tree’ does exist - it just needs to be used carefully.

Transition

For instance, last year the International Energy Agency warned of a pause in the shift to clean energy when global investment in renewables fell by 7 percent in 2017.

Governments have options to reverse this trend. One is to increase investment in energy markets directly through state-owned energy companies, and thereby crowd-in private investment; another is to create powerful financial incentives for innovation and R&D, for instance in the field of carbon capture and storage.

SMC can be a useful tool for helping governments take a lead in the energy transition and also reduce the burden of private debt.

Widespread adoption of renewable energy would be a major step; escaping from our dependency on debt-fuelled growth would be greater still.

This Author

Riccardo Mastini is a PhD candidate in political ecology in the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook.

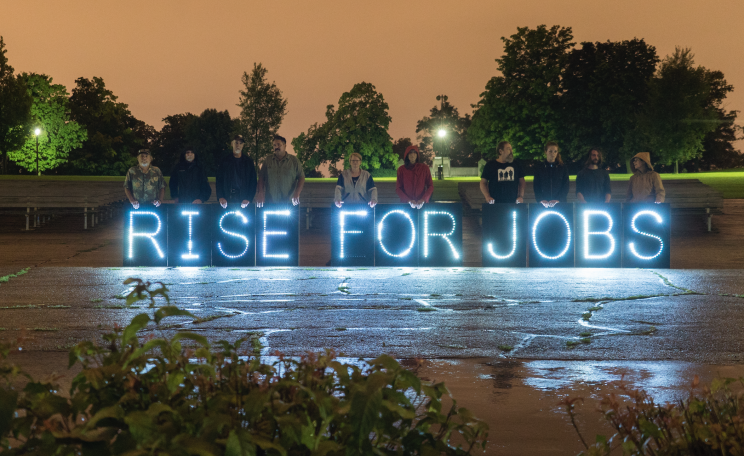

Image: Images of George Rex, Flickr.