The estimated stock of UK military plutonium holdings is about 3.2 tons – posing significant safety, security and cost challenges.

As if we already didn’t know, climate change is here, now. Widespread wild-fire and flooding has focused minds on the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) report which, perhaps unsurprisingly, confirms that as the world heats, ice stored at the poles and in glaciers melt and sea levels rise.

In short, sea-level rise is significantly faster than previously thought. Meanwhile, predicted changes to storm patterns affecting ‘storm surge’ and river flow will drive ‘combined hazards’, making flood mitigation efforts increasingly obsolete.

Because all UK nuclear military installations began operation well before global heating was considered in design or construction, near-term climate change risk to nuclear is very great.

Submerged

This is because climate change will impact nuclear earlier and harder than UK Government, Ministry Of Defence, or regulatory bodies expect, with anymitigation significantly increasing the expense of operation, decommissioning, and on-site radiation waste stockpiles.

So the key questions are: when will climate hit nuclear military infrastructure, and what will the damage be?

Well, the UK Institute of Mechanical Engineers say that UK nuclear coastal installations - together with their spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste stores - are vulnerable to sea-level rise, flooding, storm surge, and ‘nuclear islanding’. Perhaps alarmingly, they point out that these UK coastal nuclear sites could be relocated or even abandoned.

The estimated stock of UK military plutonium holdings is about 3.2 tons – posing significant safety, security and cost challenges.

And it’s not just a UK problem. In the United States, the Pentagon reports that 79 military bases will be affected by rising sea-levels and frequent flooding, including 23 nuclear installations, strategic radar stations, nuclear command centres, missile test ranges, and ballistic missile defence sites - seven of which store nuclear weapons onsite.

And this has played out in real-time when the nerve centre of the US nuclear deterrent was submerged by flood water, with recovery of the base to cost over $1 billion.

Submarines

Similarly, the US Army War College says nuclear facilities are at ‘high risk’ of temporary or permanent closure due to climate threats, with 60 percent of US nuclear capacity vulnerable to major risks including sea-level rise and severe storms.

Here in the UK, following NATO’s 2017 Strategic Foresight Analysis, which reported that climate change is a ‘threat multiplier’ involving sea-level rise, storm surge and inland flooding, the MOD determined that global warming was a Tier 1 Priority Risk.

Similarly, the UK Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre highlighted a wide range of climate threats to defence and security, noting that the entire Defence Estate is vulnerable to global heating impacts.

And as a recent MOD commissioned RAND report concludes, there will be a real need to defend or relocate UK military coastal infrastructure, with risk mitigation and repair costs significantly rising as vulnerability increases.

To put the risk in context, let’s rehearse the facts on the ground, above and below the water. The UK has circa 215 nuclear weapons, of which 120 are operational, with 40 deployed through four Vanguard nuclear-powered submarines.

Stockpile

UK nuclear warheads are designed and built at two Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) sites: Aldermaston and Burghfield. Warhead production is in the process of a major refit involving the Mark 4A nuclear warhead and large-scale building projects.

Regular transports of warhead components and fissile material, including new warhead cores and dismantled warhead components, are carried out between Aldermaston and Burghfield.

The Royal Navy has two submarine types: the Vanguard ballistic submarines and the nuclear-powered Trafalgar and Astute attack submarines armed with conventional weapons.

UK nuclear-powered submarines are fueled with highly enriched uranium (HEU), with the concentration of uranium 235 in the HEU in the submarine reactors significantly higher than in civil nuclear reactors.

UK nuclear weapons sites stockpile about 22 tons of HEU, and a further 742kg is held at various civil nuclear sites around the country.

Reactors

The Naval Base Faslane on the Clyde, and the Armaments Depot at Coulport are also key components of the UK nuclear military enterprise. Faslane berths 4 nuclear- powered Vanguard submarines armed with nuclear Trident missiles, 3 nuclear- powered Astute submarines, and an ageing nuclear-powered Trafalgar submarine.

The nuclear armament depot at Coulport consists of 16 nuclear weapon storage bunkers. Trident missile warheads and conventional torpedoes are stored at the weapons depot, where they are installed and removed from submarines. Coulport also processes and maintains the Trident weapon system and the ammunitioning of all submarine-embarked weapons.

Dreadnought nuclear submarines are being built at BEA Systems, Barrow-in- Furness, where the reactors that power the UK attack and ballistic missile submarines are assembled and commissioned.

The Rosyth Dockyard on the Firth of Forth near Edinburgh stores a significant number of decommissioned nuclear submarines, as does the Naval Base Devonport Royal Dockyard at Plymouth where deep maintenance, defueling and refueling of nuclear submarines takes place.

Nuclear reactors and cores are produced for the UK’s submarine fleet at Rolls-Royce Marine Power Operations at Raynesway.

Radiation

Highly radioactive spent naval reactor fuel is placed in MOD long-term storage ponds. The estimated stock of UK military plutonium holdings, either in the form of nuclear weapons or reserve stocks, is about 3.2 tons – posing significant safety, security and cost challenges. Amassing its plutonium stockpile since the 1950s, the MOD has yet to cost or resolve its long-term management responsibilities.

The MOD does not release the total cost of the nuclear weapons programme. However, one estimate of the cost between 2019 and 2070 is £172bn. This is almost certainly a low estimate.

The MOD assess the cost of its long-term decommissioning and waste liabilities at £18.5bn over the next 120 years. Yet, given past experience, this estimate is likely to prove very low. For example, this figure has increased by more than 186 percent over the last three years because the Treasury has changed its discount rate.

It could prove helpful to understand the reasonably foreseeable climate-driven impacts these key facilities will face - given the significant risks associated with UK nuclear military installation operations combined with their substantial radiation waste and out-of-service submarine inventories.

Storm

So, using representative sea-level projections aligned with only conservative IPCC findings, let’s go through a couple of nuclear naval base examples - Faslane and Devonport - along with their Climate Central derived flood risk maps.

These maps represent plausible threat indicators requiring deeper investigation, not least because they’re based on significantly improved coastal elevation, ocean thermal expansion, ice sheet melt, and land motion data.

That said, since the maps are not based on physical storm and flood simulations, risk from extreme flood events may be even greater – as erosion, frequency and intensity of storms, storm surge and inland flooding haven’t been taken into consideration. In other words, they may be an underestimation.

HM Naval Base Faslane

The UK’s ballistic missile nuclear-armed Vanguard and nuclear propelled attack submarines are berthed in the Faslane Naval Base, located on the eastern shore of Gare Loch in Argyll and Bute to the north of the Firth of Clyde, 25 miles north west of Glasgow.

The facility comprises a strategic nuclear base and is the headquarters of the Royal Navy in Scotland. Due to plans to increase in the number of nuclear submarines at Faslane, the MOD has applied for a very substantial radiation waste discharge increase.

The trouble is, whatever your position is on nuclear weapons, for good or for ill – looking at the Climate Central flood risk map, there seems little doubt that despite the very great concentration of nuclear military resources and radiological inventories at Faslane, significantly increased annual flooding and storm surge means that the naval base will become unviable.

Basically, the map strongly suggests that key parts of the naval base will be flooded at least once per year.

HM Naval Base Devonport

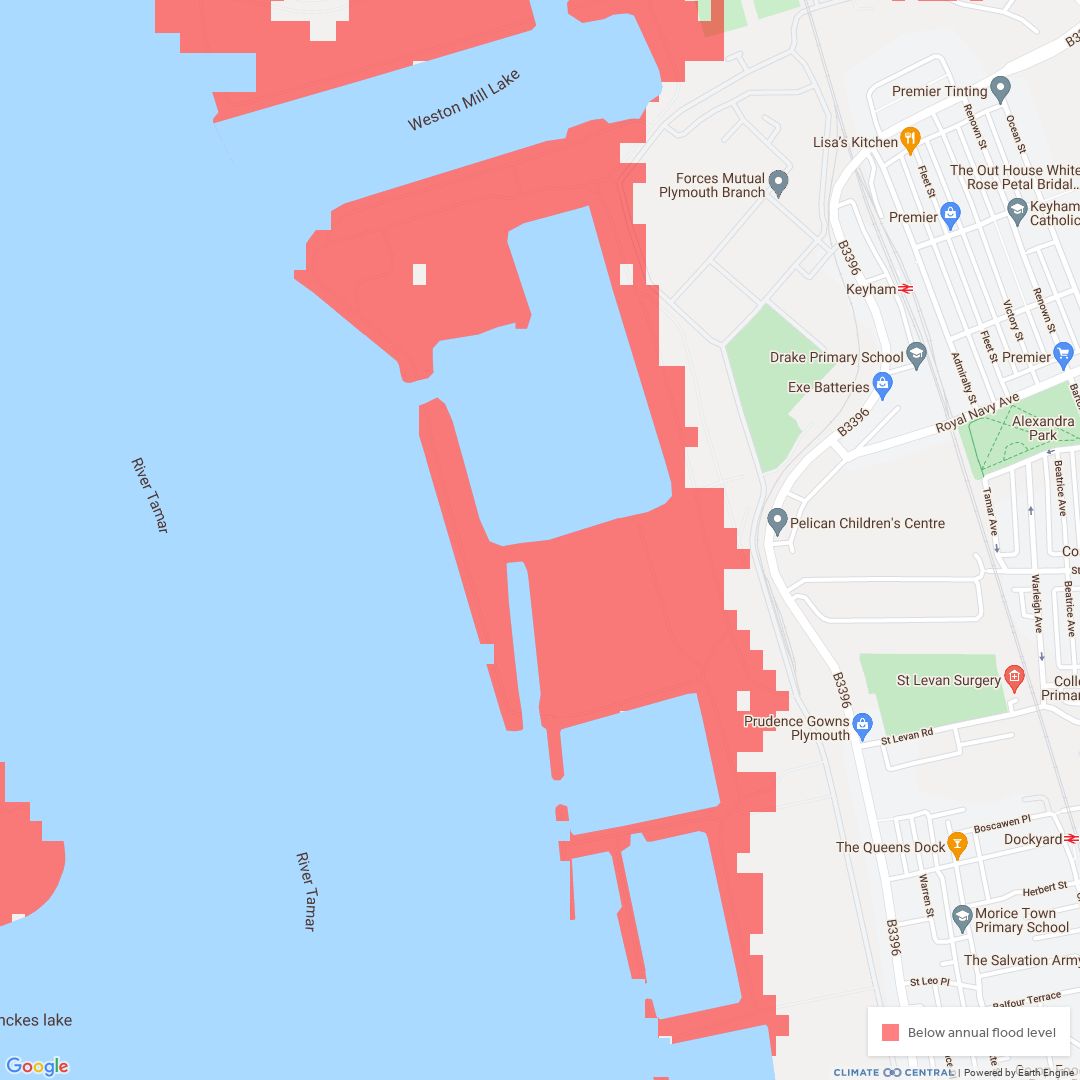

The UK’s nuclear submarines are deep-maintained, de-fuelled and refuelled at the Devonport Royal Dockyard, Plymouth – the Navy’s sole nuclear repair and refuelling facility.

Clearly, the naval bases’ current and future nuclear military operations - including submarine refuelling and de-fuelling, out-of-service submarine and radiological inventory liabilities - involves significant risk, especially given the base sits next to a large local civilian population.

However, this risk is set to ramp, given the fact the naval base will be impacted by significant climate-driven flooding and storm surge.

So What ?

Climate risk to UK nuclear military installations won’t be linear. There will be thresholds at which natural and built barriers are breached as storm surge intensity erodes flood defences.

This means that MOD and nuclear regulatory flood mitigation efforts will become obsolete, and sooner than planned.

Meanwhile, all this will involve very significant expense for UK nuclear military installation operation, waste management, decommissioning, relocation or even abandonment.

In other words, UK nuclear military is on the front-line of the climate crisis, and not in a good way. The bases are set to flood – not a good look for high-risk nuclear installations or for military policy.

This Author

Dr Paul Dorfman is an academic at the UCL Energy Institute, University College London and chair of the Nuclear Consulting Group.