Fossil fuel firms were instrumental in the development of the ISDS regime.

Environmental advocates were quick to denounce the UK decision to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). But one particularly egregious aspect of the trade deal has so far escaped attention.

The agreement’s investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism allows corporations to sue states for changes in policy and claim hundreds of millions or even billions of pounds in taxpayer funds as “compensation”.

This is particularly alarming because the UK is home to two of the biggest oil and gas firms in the world: BP and Shell. These companies are now empowered to sue Canada for taking climate action, removing subsidies, or taxing windfall profits. Equally, Canadian firms like Suncor that are active in the North Sea can sue the UK.

Greenhouse

Fossil fuel firms were instrumental in the development of the ISDS regime and they have brought hundreds of ISDS cases against governments around the world.

Just last August, UK-based firm Rockhopper Exploration won £210m in lost future profits because it was denied a permit to extract oil off of Italy’s coastline.

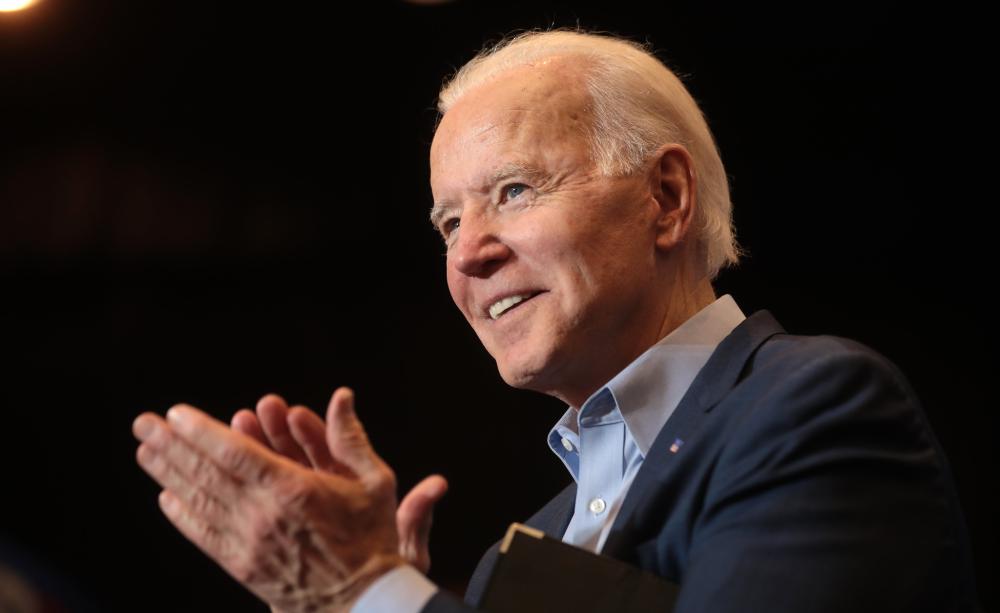

The Canadian firm TC Energy is seeking a whopping £12b in compensation for US President Joe Biden’s cancellation of the Keystone XL Pipeline.

And just a few weeks ago, the American firm Ruby River Capital Ruby River Capital launched a £16b claim against Canada over a decision to reject a new gas pipeline and LNG terminal.

The proposed development was in Québec, a member of the global Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA). The province refused the project on the basis that it would increase greenhouse gas emissions and negatively impact wildlife and the local Indigenous communities.

Investment

It's not hard to imagine a scenario in which a British firm like Shell brings a similar claim. The company is currently the largest shareholder in an extremely controversial LNG project in British Columbia. If phase-two of the project is approved, it will completely blow the province’s carbon budget.

Fossil fuel firms were instrumental in the development of the ISDS regime.

On the UK side, the threats are also very clear. Suncor, headquartered in Alberta, owns 40 per cent of Rosebank – the largest undeveloped oilfield in the North Sea. Approval of this project would make it impossible for the country to meet its climate targets.

All new and (and some existing) fossil fuel production needs to be halted to keep global heating below 1.5C as recognised by the International Energy Agency and called for by UN Secretary General Antonio Gueterres.

This is the basis of calls for a fair global phase out of fossil fuels under the auspices of a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty: an idea with backing from a number of governments, cities and a large number of civil society organisations around the world. We simply cannot afford to have expensive investor claims delaying or derailing the required phase-out of fossil fuels.

This is why the EU is actively working on exiting the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), the largest investment treaty in the world. Experts have argued that the UK should do the same.

Undermined

The good news is that, in the case of the CPTPP, it is fairly easy for the UK to eliminate the risk of ISDS cases. Australia and New Zealand have negotiated side-letters with CPTPP parties, including the UK, which “disapply the ISDS provisions.”

The new government in Chile is seeking to do the same. The British government couldadopt this approach with Canada, which would be entirely consistent with earlier statements it has made about ensuring that ISDS would not be included in a bilateral trade deal with the country.

More broadly, the UK, and all countries committed to climate action, should move to terminate the thousands of agreements with ISDS provisions that pose a particular threat to countries in the global south.

The need to build new models of climate compatible development to tackle the climate crisis cannot be undermined by the very corporations responsible for that crisis.

These Authors

Dr Kyla Tienhaara is Canada research chair in economy and environment at Queen’s University. Peter Newell is a professor of international relations at the University of Sussex.