Coral reefs cover an area of less than a quarter of one percent of all the earth’s marine environment, yet they are one of the world’s most diverse habitats, supporting one third of all fish species, and have been growing in the world’s oceans for 450 million years.

Corals are colonies of tiny individual animals, known as polyps. Formation begins when free-swimming larvae attach to new land created by volcanic activity. The larvae then grow into polyps, and lay down calcium carbonate (chalk) cups that form the reef. Coral grows only on the very thin top layer and, over time, end up sitting on top of hundreds of metres of chalk, constantly growing upwards.

A young Charles Darwin became enthralled by coral reefs on his epic Beagle voyage, and made their formation the subject of his first scientific publication. On seeing them in the Indian Ocean in 1836, he wrote in his journal, 'we feel surprise when travellers tell us of the vast dimensions of the Pyramids and other great ruins, but how utterly insignificant are the greatest of these, when compared to these mountains of stone accumulated by the agency of various minute and tender animals!'

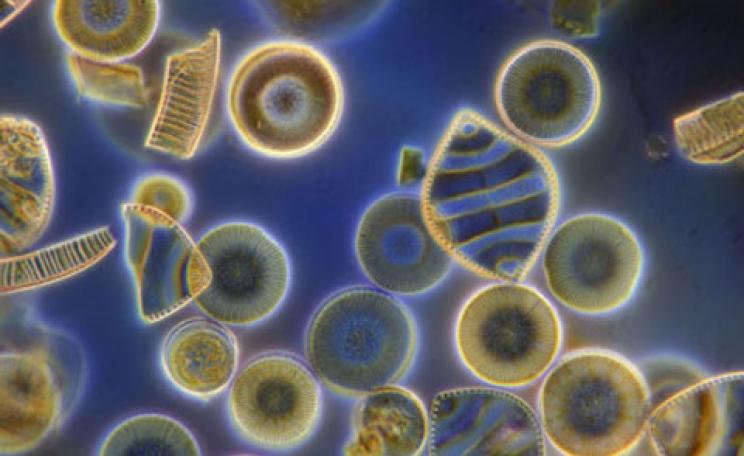

Yet these mountains cannot grow alone. Attached to the coral are microscopic algae that photosynthesise sugars. To do this, algae use sunlight and nutrients which the coral has absorbed from the water or gained from feeding on plankton. Some of the sugars are passed back to the coral from the algae, thus maintaining a mutually beneficial arrangement.

It is the algae, not the coral, that gives the reef such incredible colours, but when conditions are not optimal for algal growth, the relationship breaks down and the algae leave the coral. The reef is left pale and lifeless in a process known as bleaching, which has the potential to devastate coral reefs. Nadia Bood from WWF explains: 'Reefs are sensitive to climate change. Ocean temperatures need only to increase by one or two degrees Celsius over relatively short time periods for reefs to undergo bleaching. Coral death may occur when such stress is severe or prolonged.'

Climate change is now their greatest threat, and many scientists view coral reefs as early warning systems of a changing planet. In the words of Steve Jones in his book Coral: A Pessimist in Paradise, they have become 'a canary in the ecological coalmine'.

Coral 'phase-shifts'

Globally, 15 per cent of coral cover is under imminent threat of loss within the next 10-20 years. Reefs are also suffering because of their proximity to land.

'Rapid coastal population growth, habitat alteration and unsound tourism activities have increased the exploitation of reef ecosystems, thereby threatening the health of the reef,' says Bood. 'Siltation resulting from deforestation, erosion, dredging, mining and other land-altering activities, is a significant factor contributing to reef degradation.' Large quantities of mud and sand run-off from the land smother reef organisms, and block out the light algae need to survive.

It is clear that the algae upon which coral depend are jeopardised by man’s activities. However, if the opposite happens, and algae survive and grow a bit too well, a 'phase-shift' occurs. The reef changes from being dominated by coral, to being dominated by algae, and spells disaster for the reef, as the algae can out-compete coral for space to grow. This happens when the herbivorous fish that eat the algae, and keep its growth in check, are removed due to overfishing.

Scientists from Exeter University have demonstrated that one particular species, the parrotfish, effectively controls algae, and should therefore be targeted for protection. Lead researcher Professor Peter Mumby says: 'parrotfish consume algae and while algae are a natural part of any reef, too much algae causes problems for corals. It reduces the space available for larval corals to settle and recolonise the reef, and algae also abrade living coral, causing their growth to slow down, and sometimes direct overgrowth and death.'

The study was carried out over two and a half years in the Bahamas, where coral has suffered from bleaching. In heavily fished areas, no increase in coral cover occurred, but inside marine reserves, where fishing is banned, cover increased by an impressive 19 per cent. The presence of parrotfish allowed corals to grow freely without competition from algae, highlighting the role the fish play in the ability of coral reefs to recover from serious damage.

The identification of this important species means that governments can now put legislation in place to protect parrotfish and hence secure the future of reefs, as well as the local communities dependent on fishing. 'Most fisheries species require a complex reef habitat and this is built by corals. Parrotfish help ensure that the corals can build this habitat and therefore help ensure the long term sustainability of the wider fishery,' said Professor Mumby.

Reef mowers

Another study that set out to monitor the recovery of coral reefs from 'phase-shifts' made some surprising discoveries. A team of scientists led by Professor David Bellwood of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, deliberately triggered a shift to severe algal dominance, a 'weedy' state, on the Great Barrier Reef by covering certain areas with cages to keep fish out. The scientists then set up underwater cameras to monitor what happened when the cages were removed. Disappointingly, on particularly weedy patches, parrotfish merely pecked at the growth, and made little impression. However, another fish came to the rescue. 'These batfish showed up and got stuck into it,' said Professor Bellwood. 'In five days they halved the amount of weed. In eight weeks it was completely gone and the coral was free to grow unhindered.' It came as a surprise to the researchers, as this species of batfish was previously thought to feed only on invertebrates.

Two years later, another helpful herbivore appeared on the scene. Schools of up to 15 rabbitfish were recorded feeding at more than ten times the rate of other herbivores.

'The rabbitfish is not a fish you tend to take a lot of notice of,' said Bellwood. 'Like its terrestrial namesake, it is brown, bland and easily overlooked – but it could be very important when it comes to protecting the Great Barrier Reef. We hadn’t seen it previously at this site despite conducting over 100 visual censuses. This made its appearance in numbers sufficient to check the weedy growth all the more remarkable.'

These new discoveries made up for the disappointment of learning that parrotfish, with their ability to 'mow' algae, cannot reverse well-established, thick algal blooms. But neither can we rely on batfish and rabbitfish to save coral reefs, as they are threatened in many parts of the world. Their large size makes them attractive to spear-fishermen, and the more herbivores are removed from the ecosystem, the more the algae will flourish, causing problems for the reef.

Helping the herbivores

Total fishing bans are a successful way of protecting herbivores, as used in marine reserves, but it is estimated that 25-35 per cent of marine habitats should be no-fishing zones to provide effective protection, and this could cause conflict with growing coastal communities. Designating Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) may go some way to solve this problem. Inside these areas, fishing is allowed but restricted and harmful fishing methods discouraged to ensure sustainability of both reef and fisheries, and recent research has proved this to be effective in the long term.

Dr Elizabeth Selig from Conservation International analysed MPAs in 83 countries and found that 'on average, coral cover in protected areas remained constant, but declined on unprotected reefs. The benefits to coral generally increased with the number of years that they were protected.'

However, our climate is changing, and even the best protection will not save coral reefs from this particular threat. 'The benefits from MPAs likely will not be great enough to offset losses from coral bleaching as a result of ocean temperature increases,' said Dr Selig. 'It is imperative that we work at national and international levels to reduce the activities that cause climate change.'

Hundreds of millions of people in the tropics depend on coral reefs, not only for food and income from fishing, but also because reefs protect the shoreline by acting as a natural buffer against storms. Well-managed eco-tourism can also generate vast sums of money in some of the poorest countries in the world. It must be proven that a healthy, functioning reef is more valuable than a dead one.

Coral reefs, long a symbol of the beauty of nature, are now a symbol of its decline, but if the threats to vital herbivorous fish are addressed, there is hope for the future. Nevertheless, the threats faced by reefs today now are unprecedented in their long history.

Anna Taylor is a freelance journalist

| READ MORE... | |

|

NEWS Protecting rainforests shown to reduce poverty Introduction of measures to protect rainforests and ecosystems in Costa Rica and Thailand over the past 40 years have improved the livelihoods of the local population |

|

NEWS Urban green spaces a ‘lifeline’ for migrating birds Study points to the importance of maintaining green spaces in high-density towns and cities as migrating birds look to stop for food |

|

HOW TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE How to get involved in wildlife conservation From joining campaigns groups to making your garden more wildlife friendly, there are many ways to get involved with saving the natural world. Read on for inspiration... |

|

INTERVIEW Paul Collier: saying 'nature has to be preserved' condemns the poor to poverty Oxford Economics Professor and former head of Development Research at the World Bank, Paul Collier on reconciling romantic environmentalism and mainstream economics to help poor countries |

|

INVESTIGATION Why only the Amazonians can save the rainforest 'Saving the rainforest' has been a battle-cry of the environmental movement since its inception. But just what does that mean, how does it work, and who exactly does the 'saving'? |