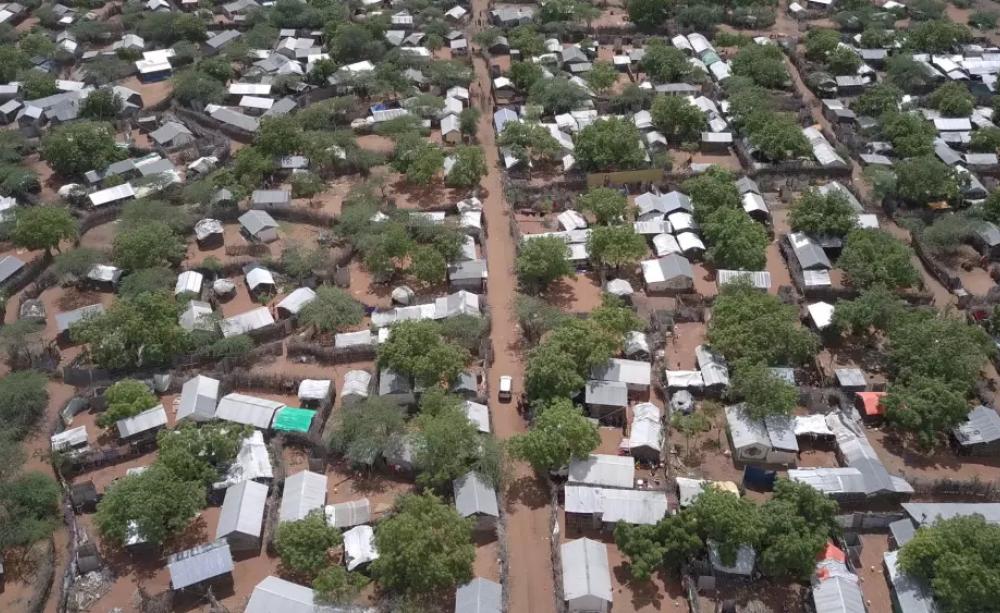

The stories of climate refugees in Dadaab exemplify the need for dignified, rights-based and sustainable solutions to the growing threat of climate-induced displacement.

More than 320,000 people have fled to Kenya’s Dadaab Refugee Complex from unlivable conditions brought on by prolonged droughts, floods, and conflict in Somalia to the north.

READ: THE ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FOUNDATION REPORT

These refugees, the victims of a climate crisis they did not cause, face chronic food insecurity, disease outbreaks, and resource shortages. As temperatures rise, these humanitarian crises will intensify, exacerbating inequality and instability.

Against this backdrop, it is still unclear how Kenya’s lauded Refugee Act will reshape the lives of these newly arrived climate refugees.

Communicating

The Act, introduced in 2021, promises to integrate Kenya’s 770,000 refugees and offers freedom of movement in ‘designated areas’.

This is considered a major step forward for refugee rights; however, the government and Department of Refugee Services, mandated to manage and assist refugees in the country, have still not revealed how they actually plan to implement these new policies.

Crucially, the government has failed to consult Kenya’s refugee communities in any aspect of the Act. According to contacts in Dadaab Refugee Camp, while representatives from the government have said they plan to disseminate information regarding the Act to camp residents, they are still waiting.

Samuel Murimi, senior programmes officer at FilmAid Kenya, expects the Refugee Consortium of Kenya, which is supposed to be communicating updates regarding the Act, to use organisations like his to disseminate information.

However, he tells Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF), he has heard nothing. “I think information is not out there 100 per cent and most of the people are not aware of the Refugee Act”, he shares.

Decimated

While Dadaab residents wait, living conditions only continue to worsen — and the climate crisis increasingly threatens to upend an already precarious situation.

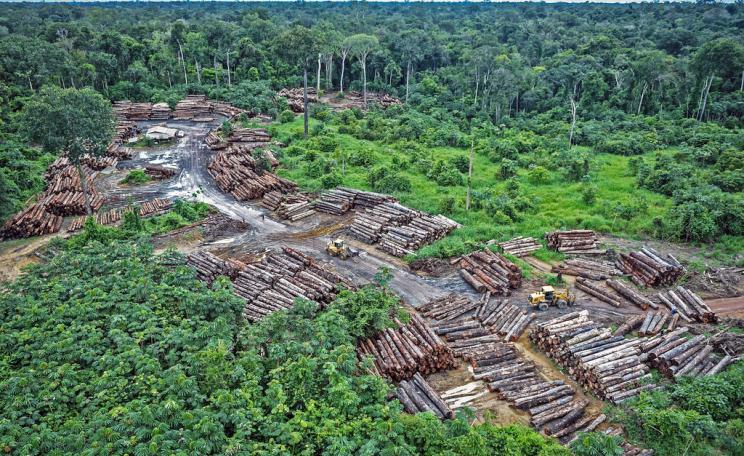

Both droughts and floods over the last few years have devastated swathes of land in the Horn of Africa and forced many to leave their homes. As world leaders start to think about COP30 in Brazil, this is a crucial opportunity to implement an international legal framework to ensure climate refugees have the same legal protections as other refugees, alongside promising legislation such as Kenya’s Refugee Act.

This legislation becomes increasingly urgent as multiplying crises have made life in Dadaab untenable for some of its residents.

In September 2022, EJF partnered with Dadaab-based journalists from Gargaar Humanitarian Radio Station and spent two weeks in the Dadaab Refugee Complex, interviewing refugees, humanitarian service providers from UNHCR and its partner organisations, among others.

Dadaab residents told EJF how drought had decimated their cattle and ruined their crops, forcing them to leave their homes and seek refuge in the camp.

Uncertain

These stories highlighted the devastating impacts of the drought in the Horn of Africa and the link between global heating and forced displacement.

EJF was led by one young Somali radio journalist, Fardowsa Gelle Sirat, who shared how statelessness had shaped her life.

“I’m not Kenyan, because I need Kenya to give me a birth certificate,” she explained. “So I’m not Kenyan, nor Somali. I’m a refugee.”

While Fardowsa has been trained as a radio journalist, she is not able to work outside of the camps. “At the end of the day, I’m not being paid the same.”

In theory, refugees like Fardowsa would benefit from the citizenship provided by the Refugee Act when it comes to employment and security, but the reality of how this will change the course of their lives is more uncertain.

Vulnerable

The government and the Department of Refugee Services have still not released information regarding the specifics of how refugees will be able to integrate into local communities or, for example, purchase property.

Transforming the overcrowded and underfunded camps into settlements with greater freedoms will, inevitably, require significant funding from both the government and relevant stakeholders.

However, Dadaab is already suffering the consequences of decreasing funding. Fardowsa shares that the camp administrators have struggled to provide even the basics for newer Somali refugees.

As global heating worsens, the number of arrivals in Dadaab is only set to increase. In Somalia’s largely agro-pastoralist economy, which is being hit the hardest by the multiplying droughts and floods, livestock alone generally accounts for around 40 per cent of GDP.

Around 69 per cent of Somalia’s population is estimated to live below the poverty line. In 2021, Somalia was ranked the world’s most vulnerable country out of 185 countries studied by the University of Notre Dame.

Buried

The climate crisis and various extreme weather events have pushed Somalia’s large population of farmers into ever-increasing desperate situations, as their crops fail and the livestock dies.

Halima Hassan Ibrahim, for example, fled to Dadaab from the Bu’ale District of Somalia in the Juuba River Valley when consecutive years of drought dried up her farm and killed her livestock.

EJF met the disabled single mother of seven during the field trip, when Halima was living on the outskirts of Dagahaley with her children in makeshift accommodation and without regular access to clean water or sanitation facilities.

Halima said: “We suffered from four years of drought. We used to cultivate our fields. We had 10 cows and 50 goats. All of the cows and goats died and everything else was destroyed and because of that, we came to the refugee camps. I’m a mother and a father for my kids, and I don’t have anything for them.”

Khaira Hassan Mohammed has lived in the camp since the 2011 famine, and is now 99 years old and in need of medical care. She had six children, but she has buried them all since arriving. When asked about her expectations for the future, she said: “Don’t ask about my life. I don’t receive anything, nobody helps me.”

Living

A year after EJF visited Dadaab, the rain arrived. However, instead of this being a cause for celebration, the downpour turned into floods which led to the same outcome: hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees forced to flee their homes. The knock-on effect of the floods in Dadaab has been disastrous.

The most recent analysis from the Office of the Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs states that floods between April to June of 2024 have impacted over 200,000 people and displaced almost 40,000.

This comes following the floods at the end of 2023, where El Nino fuelled heavy flooding which, in turn, led to the government of Somalia calling a state of emergency in some areas. By the end of 2023, 2.48 million people were impacted and around 1.2 million displaced from their homes.

While refugees displaced by floods in Somalia arrived in Dadaab through 2023 and 2024, 20,000 pre-existing residents were also displaced by rising water levels by May 2024. At that time, around 4000 refugees who had been further displaced were staying at six schools across the camps.

When we spoke to Fardowsa again in October 2024, she clearly set out the impact of the floods on living conditions in Dadaab. “There is no quality of life in Dadaab throughout this year. [The floods] have only increased the number of refugees. The little resources from the agencies are not enough, with this hard life and climate.”

Dignified

FilmAid’s Samuel reiterated what Fardowsa had shared about the insufficient amount of food, water and medical supplies. “This has become a nutritional issue. The funding went down, the health centre has been affected. It can’t get enough drugs that can be distributed to refugees.

"When they get a prescription, they go to get their drugs over the counter, but they don’t have the cash. That means their life is at stake.”

As the situation in Dadaab grows more desperate, the real perpetrators of the climate crisis fail to step up and take responsibility.

Somali climate refugees are on the frontlines of the climate crisis, yet in 2019 Somalia had a per capita carbon footprint barely one-fifth of the EU’s, and the entire continent of Africa only contributes around 3.8 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The stories of climate refugees in Dadaab exemplify the need for dignified, rights-based and sustainable solutions to the growing threat of climate-induced displacement.

Protection

The Refugee Act in Kenya is a welcome step forward, but the government must make sure it becomes a reality. Beyond this, to transform the lives and futures of those on the frontlines of the climate crisis, global and national-level human mobility policies must consider the impacts of global heating.

Conversely, climate change mitigation and adaptation policies must consider impacts on human mobility. There is a growing international acceptance of the link between global heating and human mobility, yet different actors and institutions disagree on how to conceptualise and act on this emerging issue.

Climate displacement can be framed as a security threat, as a humanitarian crisis, or as a climate adaptation strategy — how it is framed will influence the shape of global governance solutions for climate displacement.

Yet without the urgent development of a robust framework designed to effectively protect those most vulnerable to the climate crisis, the reality is that millions of people across the world will remain in effect deprived of their most basic human rights.

Legislations, like Kenya’s Refugee Act which proposes integration and combats statelessness, are crucial for transforming the lives of refugees, but they must be complemented by an international legal framework for the protection of climate refugees. As the consequences of climate breakdown continue to escalate, we must do what we can to better support those most vulnerable to its impacts.

This Author

Steve Trent is the chief executive and founder of the Environmental Justice Foundation.